I now present my interview with Frank Harvey, professor and author of

Explaining the Iraq War: Counterfactual Theory, Logic and Evidence, which won the

2013 CPSA Prize in International Relations. Learn more about Frank below:

Welcome to The Update, Frank. Please tell the readers a little about yourself.

I grew up in Montreal and married an amazing Montrealer I met at McGill University (in the pub, playing pool). I completed my PhD dissertation in 1992 on US-Soviet nuclear rivalry, and started at Dalhousie University (same year) teaching world politics, international conflict and US foreign policy. I just completed a two-year term as Associate Dean (Research) at Dalhousie and am currently on sabbatical working on two books: one on the application of US coercive diplomacy (deterrence/compellence) in Syria and other asymmetric conflicts over the past two decades (addressing the question of whether ‘fight for credibility’ makes sense), and a second book on US-NATO cooperation on ballistic missile defence. We have a 19 year-old daughter, Kalli, completing a degree in the Faculty of Management at McGill, and 16 year-old son completing the IB program at Citadel High, Halifax.

What got you interested in counterfactual history?

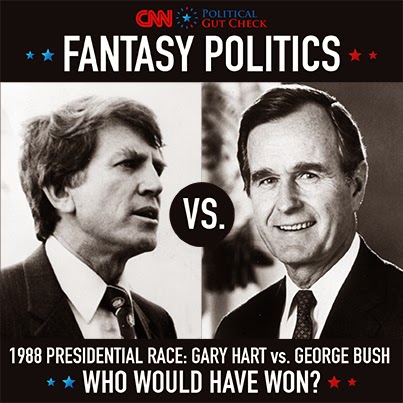

If I had to pinpoint the primary motivation it would be this: despite the importance of understanding what happened in the lead up to the Iraq war, the most widely accepted version of that history (and still the preferred account) was becoming increasingly entrenched over time, despite its many obvious logical and factual errors. Scholars, journalists and foreign policy experts I respected began to offer a common historical account of this period that did not mesh with my recollection of the facts, arguments and decisions as they unfolded at the time. This popular account remained powerful not because it was right (or factually correct), but because it was comforting and useful. People are comforted by the belief that changing the leader would be sufficient to avoid these types of wars, and politicians on both sides (many involved in key decisions leading to the Iraq war) are more than happy today to continue blaming a few neoconservatives. This consensus also led to dozens of ‘counterfactual’ claims, by prominent opinion leaders, that if it wasn't for a few more hanging chads in the 2000 US election the world would be a very different place today. I decided to test this popular counterfactual argument, and the results are pretty devastating.

What is Explaining the Iraq War: Counterfactual Theory, Logic and Evidence about?

Briefly, any theory we might offer to explain the cause of some event, like the 2003 Iraq war, can be easily re-framed as a counterfactual argument. For example, if I am convinced that X caused the war, then I am also likely to be pretty confident that war would not have occurred if X didn't happen. In other words, if X is necessary for war, then the absence of X would be sufficient to avoid war - that is the essence of counterfactual historical analysis.

Now, consider how this logic applies to the most common explanation for the 2003 Iraq war: if Bush and his neoconservative advisers were directly responsible for fabricating the weapons of mass destruction intelligence that justified the war, then it stands to reason that an Al Gore victory in the 2000 presidential election would have been sufficient to steer the country down a different path (this is the standard story). But what if the historical record clearly shows that Al Gore and almost every other Democrat ‘agreed’ with the faulty intelligence on Saddam’s WMD (much of it collected by the CIA and UN weapons inspectors during the Clinton-Gore administration)? What if the record shows that Gore ‘endorsed’ most of the key decisions taken by George Bush and Tony Blair to deal with Saddam during from 2002-2003? What if the evidence confirms that neoconservatives actually ‘lost’ many of the key policy debates during this period? In this case, counterfactual analysis leads to a better explanation of the complex combination of domestic and international factors that combined to push the US and UK closer and closer to war.

The book’s main conclusion (there are many) is this: contrary to popular opinion, leaders of large, developed liberal democracies have very little control over the foreign and security policies they implement. In fact, many of these leaders typically adopt the policies of their predecessors, notwithstanding their own ideology, personality, values or belief systems. Replacing a leader, in other words, won't change much, and counterfactual historical analysis can play a major role in demonstrating this important point. Foreign policies usually have more to do with a complex combination of domestic interests and international pressures that leaders attempt to balance on behalf of the states they govern. In fact, one of the more important points I raise in the book’s conclusion deals with the concept of "projectibility" - i.e., using counterfactual analysis to predict future foreign policies.

If my counterfactual explanation for the Iraq war is sound (i.e., neoconservatives were irrelevant and Al Gore would have made the same decisions as president), then this pattern should also apply to future US foreign policies embraced by very different presidents. As expected, Obama's foreign policies (e.g., the use of drone strikes, keeping Guantanamo Bay prison open, the NSA’s surveillance program, homeland security policies, Obama’s decision to intervene in Libya and to threaten Syria, etc.) look very similar to Bush's. In fact, the speeches by Obama and Kerry (in congressional testimony) defending the planned Syria strikes were virtually identical to those put forward by Bush and Powell prior to Iraq - they are all defending the same coercive diplomatic strategies, national interests and principles. The only difference in the Syria case is that Assad and Putin didn't miscalculate, because they had the benefit of seeing the effects of miscalculations by Slobodan Milosevic, Saddam Hussein and Muammar Kadhafi (they all underestimated US resolve).

What are some of the pros and cons of using counterfactuals when studying history?

Biggest Pro: Counterfactual analysis is not just another method for comparing different interpretations of major historical events – the approach is fundamental to any serious historical or social scientific inquiry committed to evaluating competing explanations of major events in history. And valid ‘causal’ explanations for any event are essential to understanding (and implementing) effective foreign policies and solutions, especially when identifying lessons learned following major foreign policy failures. For example, weak explanations of the Iraq war that blame neoconservative ideologues are likely to downplay the scope and nature of intelligence errors prior to the war, because faulty intelligence, they would argue, had almost nothing to do with the decision that were taken. The real problem, according to those who embrace the standard account, was the politicization of the generally sound WMD intelligence that neoconservatives re-framed, exaggerated and exploited to support their pre-determined invasion plans.

The solution is simple: get rid of the neoconservatives and everything is solved. But if the standard account is wrong, then the policy advice is unlikely to solve and could actually exacerbate the central problems confronting the American intelligence community. Now, if the real problem was the generally accepted but mistaken intelligence estimates on Iraq’s WMD, compiled over decades of UN weapons inspections and documented in numerous US, UK and UN reports, and if these systemic intelligence errors explain the decisions by the US and UK leading to war, then the solutions are far more complex and difficult to implement. Getting the history right is essential to fixing the real problems facing the US intelligence community and avoiding similar catastrophic and costly errors in the future. Counterfactual analysis leads to better policy advice.

Biggest Con: everyone uses counterfactual analysis, including (ironically) a majority of scholars who remain highly critical of the approach, but they rarely acknowledge or understand how central it is to their own analysis and conclusions. Many of us (including world renowned historians) have a somewhat simplistic understanding of the approach and tend to dismiss it or reject its application without any effort to appreciate its potential contributions to historical analysis. Why is this a con? Because it makes it exceedingly difficult for me to persuade people that their preferred explanation for the Iraq war is essentially wrong, despite the overwhelming fact-based evidence to support my argument. Why is this a con? Because, as explained in the ‘biggest pro’ above, if we get the history wrong we are unlikely to be able to resolve the main problems that led to the Iraq war. History is likely to repeat itself.

Historian Richard J. Evans has recently come out in opposition to counterfactuals. Do you think he has made any good points and are counterfactuals really as popular as he says?

Yes, I read

Evans’ book and

Guardian article (and

your response…thanks for the nice plug, by the way) and I am familiar with his criticism of counterfactual historical analysis. I actually ‘share’ many of his views on what usually passes as counterfactual history, particularly the tendency to privilege contingency at the expense of careful analysis of the many pressures that typically play a role in major decisions. And I ‘agree’ with his major criticisms of counterfactual analysis outlined in his book and summarized in his recent Guardian piece, for example:

- Counterfactual history “…threatens to overwhelm our perceptions of what really happened in the past, pushing aside our attempts to explain it in favour of a futile and misguided attempt to decide whether the decisions taken…were right or wrong.

- “…leads not to historical understanding but to all kinds of wishful thinking, every hypothesis political in motivation.”

- “Counterfactuals…open up the past by demonstrating the myriad possibilities, thus freeing history from the straitjacket of determinism and restoring agency to the people.”

- “Yet this ignores, of course, an infinite number of chances that might have deflected the predicted course of events along the way.”

- “…almost always treat individual human actors – generals or politicians, in the main – as completely unfettered by these larger forces, able to make decisions without regard to them in any way. And yet this simply isn't the case.”

- “…regress into a ‘great man’ view of history that the historical profession abandoned decades ago.”

- “…‘kings-and-battles’ view of the past…is thoroughly outdated – outdated because it is crudely simplistic and desperately unsophisticated.”

- “In practice, of course, every historian tries to balance out the elements of chance on the one hand, and larger historical forces (economic, cultural, social, international) on the other, and come to some kind of explanation that makes sense.”

Again, I agree with these points. But they apply to ‘weak’ counterfactuals not to ‘all’ counterfactual analysis, which is why I fundamentally disagree with his conclusion that “counterfactuals aren't any real use at all.” This may appear on the surface to be a pretty serious contradiction, but it isn’t. And I am hopeful that anyone who reads my book will see the difference between ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ counterfactual histories and appreciate the important role counterfactual analysis can play in challenging seriously flawed (but very popular) ‘historical’ and related 'counterfactual' accounts of the war (they are logically connected, as I explain in the book). I hope readers will also notice the effort I invested in collecting historical 'evidence' and 'facts' to defend my account of contemporary US history and the key decisions that led to the Iraq war.

So with all that being said, what is the best point of divergence to prevent the United States from going to war with Iraq?

No question - it was 9/11. Take out 9/11 and it would have been virtually impossible for ‘any’ US administration to: convince UK to join them, get UN Resolution 1441 passed, get congressional authorization to deploy troops, obtain any European support for the initiative, etc. All of these prerequisites would not have been present in the absence of 9/11, and all related imperative to deal with Iraq’s WMD threat would have been absent.

There are a lot of President Gore alternate histories, but few President Kerry timelines. Why do you think that is?

The more interesting alternate history or counterfactual arguments usually focus on changes that would have produced significant, path breaking effects on history. The Gore counterfactual is interesting because of the overwhelming (but mistaken) consensus that his victory would have had a major effect on the course of US foreign policy. But Kerry’s victory would have occurred after 9/11, after Afghanistan and after Iraq - all of the big (historically interesting) decisions were already taken, so his impact would have been negligible.

What are you reading now?

Mostly books on contemporary US foreign policy, coercive diplomacy, deterrence theory and ballistic missile defence.

.jpg)